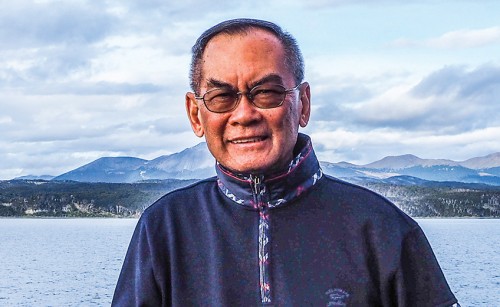

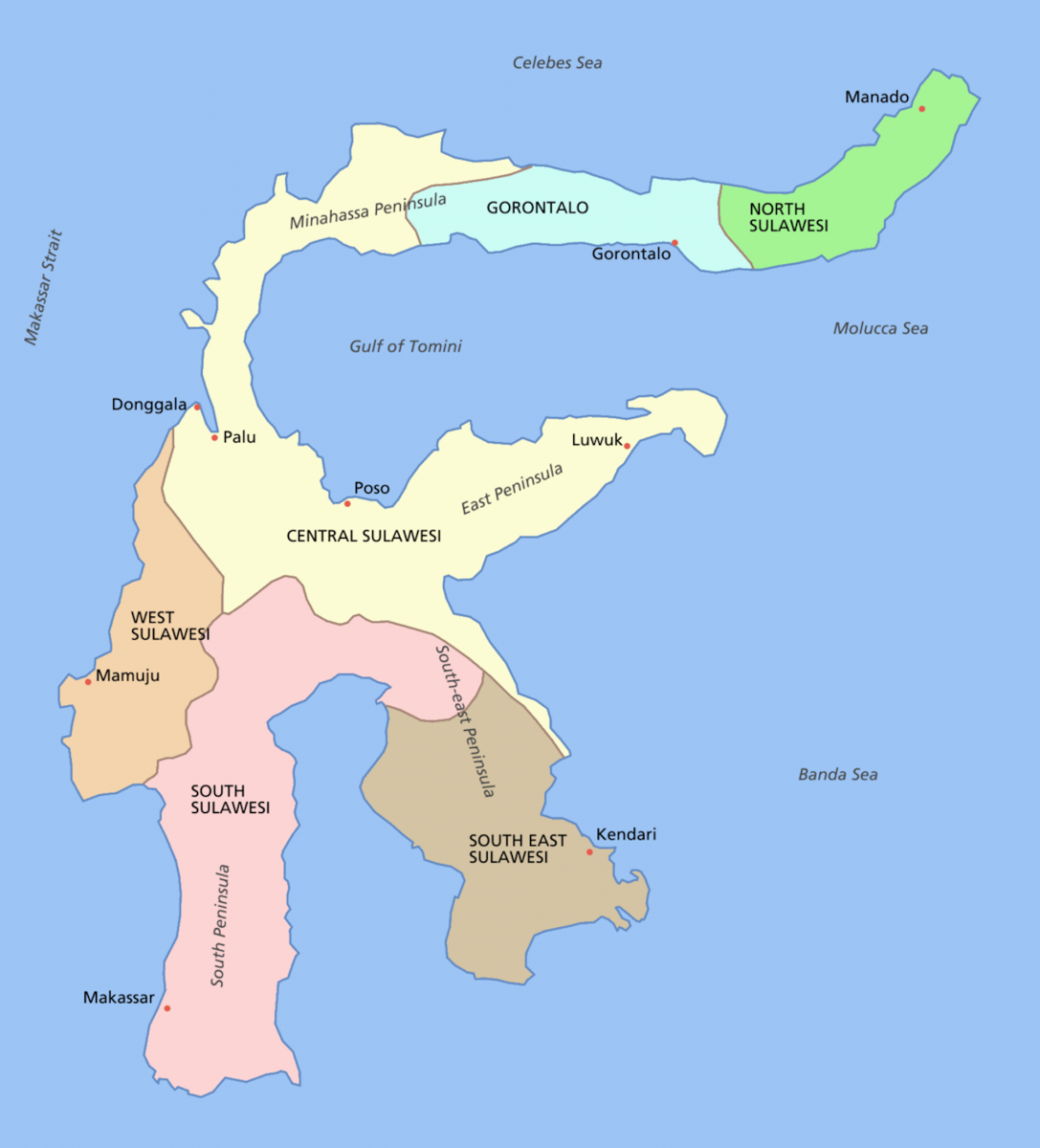

On a recent trip before the Covid-19 lockdown set in, I travelled to the island of Sulawesi, Indonesia’s fourth largest island and the eleventh largest in the world. Located in the Greater Sunda Islands archipelago and with its enormous size, 74,600km², I began my exploration in North Sulawesi and left Central Sulawesi, West Sulawesi, South Sulawesi and Southeast Sulawesi for another time. While on a map, Sulawesi does not look very far from Thailand, reaching Gorontalo in North Sulawesi did take two days of travel.

I flew from Bangkok to Denpasar on the island of Bali and after staying there overnight, the next morning I continued the trip on a domestic flight from Denpasar to Makassar in South Sulawesi where I connected with a flight to Gorontalo. From there, I embarked on a three-hour drive on a combination of paved and unpaved country roads to reach the village located adjacent to Nantu Nature Reserve, my final destination.

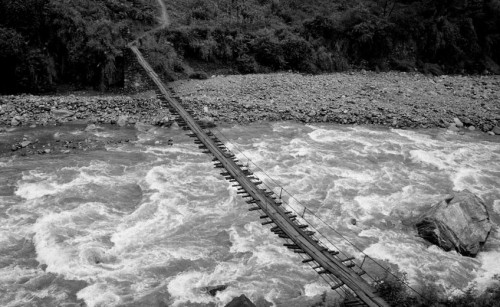

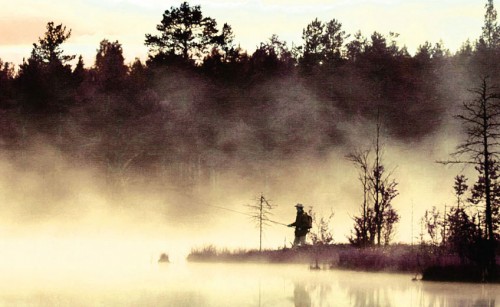

I had booked a home-stay accommodation in a local house, which was quite comfortable. The next morning, I ventured out with a local guide on a twenty-minute walk through a sugar-cane field and coconut orchard after which we arrived at the Nantu River. We waded across the knee-deep, forty-meter wide river to reach Nantu Nature Reserve on the far shore.

You might be wondering why I had taken such a long and strenuous journey to Nantu Nature Reserve. Well, it is the most accessible of only four locales in the world where the babirusa, a rare species of mammal, lives in large number. Next, you may ask what is so special about babirusas and why did I yearn to see and photograph them.

Babirusas have a unique, prehistoric appearance, the combination of a pig and a deer to form this creature also known as the “pig-deer”. The name babirusa is the combination of the Bahasa Indonesian words babi, which means pig, and rusa which is translated as deer. The main feature of the adult male is a pair of long canine tusks curving upward until they pierce the animal’s forehead. It also has another pair of lower sharp-pointed canines, which serve as defensive weapons. Only the males have such canines.

%202.jpg)

I would also like to mention that besides being rare, the babirusa is classified as a vulnerable species by the International Union on Conservation of Nature (IUCN). To safely observe babirusas and not disturb them, we sat in a blind that could accommodate up to three persons. The blind was located at the rim of a large salt lick where a stream flowed by. So, I could silently take photos and videos of the wildlife coming there. That particular salt lick was frequently visited by many babirusas, both male and female adults and young ones. Those sights made all the problems I had faced to get there well worth it.

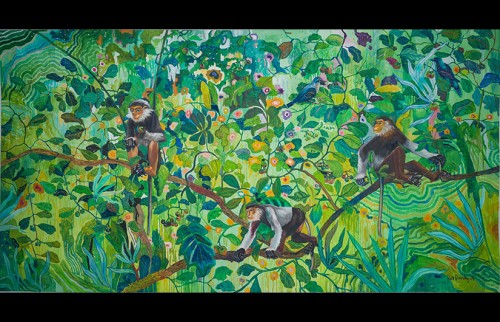

In addition to our sightings of babirusas, we were also very lucky to see a troop of about a dozen very short-tailed monkeys that unexpectedly appeared at the salt lick foraging for sustenance. I had never seen these monkeys before and was told by my guide that they were Heck’s macaque, which sometimes came to this salt lick. They are endemic to North Sulawesi and also classified as a vulnerable species. I regarded their surprising presence as truly a bonus for my visit.

I visited the same blind the next day as well and sighted many of the same as well as other babirusas. The Heck’s macaques, however, did not return. My guide told me that another species that frequently foraged at the salt lick was the dwarf buffalo. Unfortunately, no dwarf buffalo appeared during the two days either.

During our walk back to Nantu River to cross once more over to the other bank, I passed a giant somphong tree on which my guide spotted a Sulawesi three-horned beetle climbing on the trunk. This black beetle was a male with three horns and was about 110mm in length. He said he knew it was male because females lack the horns.

On that same somphong tree, I also found a male and female Sulawesi tree trunk spider, 10 to 18mm in length. They were quite hard to spot as they camouflaged themselves among the bark as is shown in photos. A closer look at the two spiders let me distinguish their gender, as the female is bigger.

Besides the native mammals and insects I mentioned, the Nantu forest is also home to many species of flora. I sighted and photographed a group of fungi cup red mushrooms and two kinds of unidentified flowers along the trail between the blind and the river.

After two days in Nantu Nature Reserve, I returned to Gorontalo to board a forty-minute flight to Manado, the capital of North Sulawesi. From Manado, a two-hour drive by car took me to Tangkoko Nature Reserve where I planned to stay three days. In Tangkoko, my focus was on seeing four endemic and threatened species of wildlife – the critically endangered Sulawesi Black Crested Macaque, vulnerable Sulawesi Bear Cuscus, vulnerable Spectral Tarsier and vulnerable Sulawesi Red-knobbed Hornbill.

This time, with two local guides, we left Tangkoko Lodge at four pm and reached Tangkoko Nature Reserve in just ten minutes. Only a few minutes after we passed the gate, the guide driving stopped the car, pointed at a clump of trees twenty meters from the road and said, “Green-backed Kingfisher.” I followed the other guide out of the car and tried to spot the bird amidst the dim light among the trees. I finally saw the green-backed kingfisher perched on a tree branch unperturbed by our presence. The bird is native to Indonesia, particularly in North Sulawesi and Central Sulawesi, and it is classified by the International Union of Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as a near-threatened species.

After having snapped a few shots of the kingfisher, my first wildlife sighted at Tangkoko, we continued deeper into the forest until we reached the reserve office and a parking lot where we parked and set off on foot along a trail searching for our main objective, the Sulawesi Black Crested Macaque.

.jpg)

Soon the guide leading our trek halted in front of a tall tree and pointed at a lizard on its trunk only two meters away. He told me that it was a Sulawesi Lined Gliding Lizard, endemic to Sulawesi. I was quite fortunate as the easiest location to spot this lizard is in Tangkoko. The lizard can take off from one tree and glide more than sixty meters as it swoops downward to a spot just two meters below. It has flaps that it can extend at will from both sides of its body, which enables it to glide downward.

We then continued deeper into the forest and soon stopped at another massive tree. One of my guides then looked up into canopy overhead and pointed at a strange looking primate staring down at us. I asked what kind of monkey it was. He said it was not a monkey but a Sulawesi Bear Cuscus, a marsupial, a mammal with a pouch at its belly to carry and rear its young, similar to the kangaroo, wallaby and koala in Australia. The Sulawesi Bear Cuscus is the only marsupial found in Sulawesi and is classified by the IUCN as a vulnerable species.

The Sulawesi Bear Cuscus has a body length of 61cm and a prehensile tail 58cm long which can firmly grasp a tree branch so it can find and eat food while hanging in the trees hidden in the high jungle canopy safe from predators. Its main diet comprises leaves, flowers, and raw fruits.

The discoveries I made I’m happy to share with you through the accompanying photographs. Meanwhile, I continued my adventure and search for the Sulawesi Black Crested Macaque at Tangkoko Nature Reserve in North Sulawesi.